Five Eyes wide shut: now is the wrong time to pause in shaping Australia’s intelligence agencies

In a world where big powers resort to bullying, aggression and outright war, intelligence is a vital for the security of smaller nations, as Ukrainians know only too well.

So Australians need to be confident we are maintaining our intelligence edge.

That’s why in 2023 the government was right to commission an independent review into the nation’s intelligence agencies.

It’s also why there is now no reasonable excuse to keep withholding the review’s conclusions from the public.

The review leads, eminent former officials Heather Smith and Richard Maude, submitted their report to the government eight months ago.

Australia governments have a bipartisan tradition of rigorous reviews of intelligence capabilities, transparency in releasing unclassified versions of the findings, and promptness in indicating which recommendations will be taken up.

This was the case in 2004, following the intelligence and policy failures of the Iraq War, in 2011, when terrorism and economic issues were high priorities, and again in 2017, when a worsening strategic environment triggered greater coordination and resourcing of the intelligence community.

In 2020, a review of intelligence laws ran to 1300 pages, and that was just the published version. It was candour by the pallet load.

If the Albanese government has a sound reason to break that cycle of openness, it should say so.

But as things stand, the silence seems inexplicable, in the interest neither of the public nor the nation.

Instead, this is a time when optimising our nation’s intelligence capabilities for a turbulent world should be an urgent priority.

Signals from the second Trump administration raise disturbing questions.

A capricious and transactional approach to intelligence sharing will do severe harm to this most trust-based element of security cooperation.

It was bizarre enough for Trump adviser Peter Navarro to reportedly suggest expelling Canada from the Five Eyes network as a pressure tactic on other issues, He subsequently denied such reports.

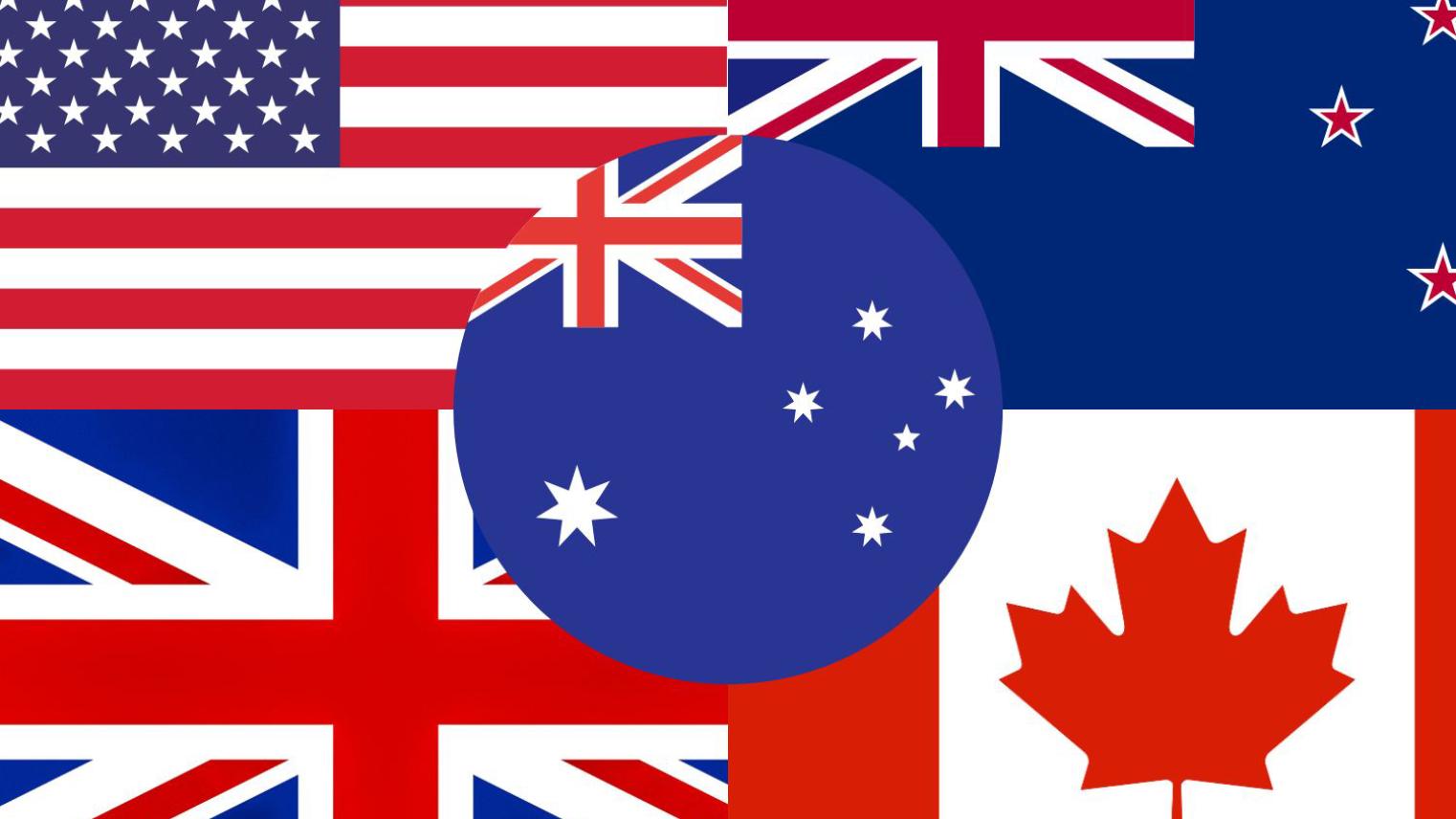

The Five Eyes, which also includes the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, evolved from cooperation the Second World War to become the most successful intelligence-sharing partnership in history.

But the main hammer blow so far to America’s reputation as a reliable intelligence partner has been the suspension of sharing battlefield intelligence with a besieged Ukraine.

This is a cruel lever to compel president Zelensky to end his nation’s war of resistance to Russian aggression on Trump’s terms (and presumably to say thank you).

The United States has even directed a private company, Maxar, to restrict Ukraine’s access to its high-grade commercial satellite imagery.

Even without these developments, intelligence partners may quietly think twice about what sensitive information on Russia they should share with this US Administration, given who some of its most senior intelligence consumers happen to be.

These include not only president Trump and vice-president Vance, who currently seem more aligned with Putin’s Russia than with Ukraine in how they want to dictate the fate of Europe.

The most powerful US intelligence official, Tulsi Gabbard, is on record expressing views closer to Kremlin propaganda than the assessments of the formidable analytical community she now leads.

Where does all this leave Australia?

In its public utterances, Canberra is understandably keeping its diplomatic cool in speculating about the future of the alliance with Washington.

The alliance is grounded in convergent interests. Under the 1951 ANZUS treaty, which Australia initiated, both sides commit to consult and ‘act to meet the common danger’ of armed aggression in the Pacific.

Australia also derives great benefit from US military technology, a bond that the AUKUS nuclear-powered submarine deal has been designed to take to the next level.

The United States has increasingly looked to Australian territory as a staging point and bastion for its forces in future security crises, with the point being to deter China from starting a conflict at all.

Despite the harm Trump’s tariff threat may bring, the economic relationship between Australia and the United States is vast and deep. America is our largest investment partner by far. And, whatever their flaws, our two open societies have long had much in common.

But closest to the heart of what makes the alliance special is the privileged sharing of intelligence.

No prudent Australian government will seek to jeopardise it.

However it would be irresponsible to imagine that an America First hand on the intelligence tap will never be a problem for us.

This means that now is precisely the wrong time to pause in shaping the future of Australia’s intelligence agencies.

For a disconcerting future is already here: from radical technological transformation to the flood of disinformation, from the impact of natural disasters worsened by climate change to the erosion of social cohesion, from the trans-Atlantic strategic rift to Chinese warships doing an intimidating lap of our continent.

Intelligence capabilities are a nation’s decision advantage. Properly investing in them is always a bargain in the long run.

Our intelligence agencies operate under high standards of governance and accountability, with rigorous oversight from statutory bodies. There’s good reason to believe they are performing well.

But is our intelligence community postured for the danger and disruption ahead? Does it have the funding and the next-generation talent it needs? Do we have the balance right between sovereign capabilities and reliance on America?

How are we doing with partners beyond the Five Eyes, such as Japan and Europe? With the private sector now ahead of government in intelligence technologies, what scope for trusted and agile collaboration?

Is the best intelligence still the secret stuff? Should we set up an agency that just specialises in drawing intelligence meaning from plentiful open-source information?

Why not share strategic intelligence judgments with the public, on the model of the threat assessments pioneered by ASIO chief Mike Burgess?

How effective is old-school human spying in an age of digital footprints and biometric identification? Are legal oversight mechanisms keeping pace with technological change?

Australians deserve answers to these questions and more. It’s not too late for the government to make good on its original willingness to ask them.

Professor Rory Medcalf is Head of the National Security College at the Australian National University.

This article was originally published in the 12 March edition of The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age.